Hitory has a habit of putting together a small number of people in every generation who uniquely have the vision and determination to shape new horizons for society, for better or worse. Lennon and McCartney conspired to change the shape of popular youth culture in the mid-20th century; Lenin, Mao Tse Tung, and JF Kennedy created a new 20th century order of geopolitics, which continues to shape our destinies. In Ireland T. K. Whitaker, an Taoiseach Séan Lemass and Brendan O’Regan helped shape modern Ireland with their vision and pragmatism.

Brendan honed his mesmeric diplomatic skills in the fledgling Shannon incubator, which breathed life into a previously isolated, wasteland forgotten by the new Irish state. As he tackled the pressing social and economic challenges of persuading local, national and international leaders of the powerful potential of the region, he noted in his famous black book the names of leaders of influence on whom he would call when his peacebuilding era beckoned.

From the early 1970’s, Brendan felt an instinctive need to identify with the embryonic peace movement in the North, but quickly recognised that more structured, managed approach was needed, and on a North-South basis.

He invited TK Whitaker to chair a conference in 1978 from which Co-operation North emerged. The great statesman distilled the complexities of the challenge into a simple, digestible concept, “It is a very obvious fact that the North and the South have to get to know each other better”.

Brendan recognised that peacebuilding required the same professional approach that war-making did namely, financial and management expertise. While he successfully enlisted the financial backing of the four main Irish Banks and Carroll’s of Dundalk, he persuaded the European Commission that the new organisation was predicated on “the practical idealism” that inspired the founders of the EEC. It needed experienced personnel, which the fledgling charity couldn’t afford. As a result of Brendan’s efforts, the Commission seconded three senior Irish Commission officials on full pay as CEO’s of Co-operation North at no cost to the latter organisation. Other similar secondments from the banks and semi-state bodies,

North and South, ensured the professional management approach to peace- building on which Brendan had insisted.

Brendan enlisted leading business people from both sides of the border under the principle of non-political, professionally managed co-operation. The unique focus was on the North-South axis. Lack of contact gave rise to lack of information, and in this void prejudice, suspicion, animosity and conflict thrived.

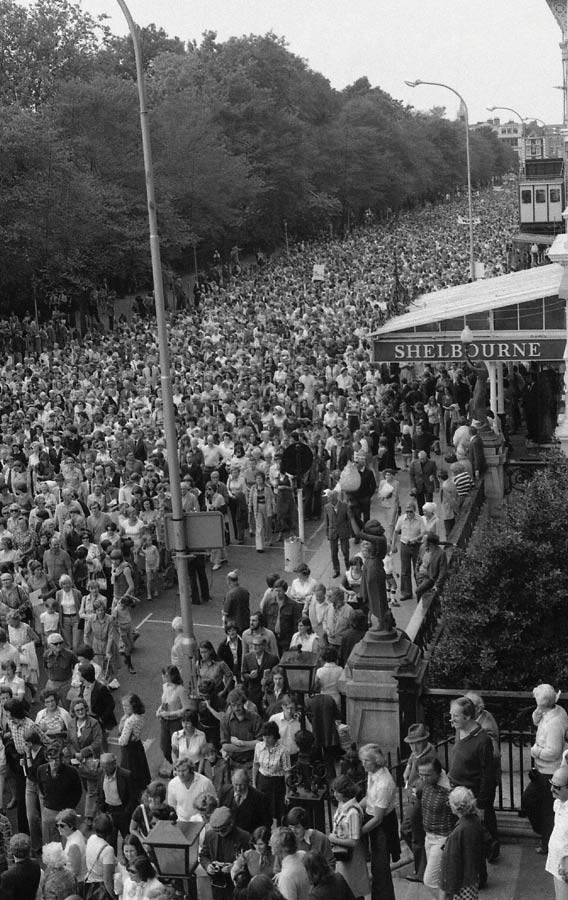

Large scale programmes were developed by Co-operation North under the basis of a simple “contact hypothesis”- the border had been successful in creating little or no contact between the Nationalist and Unionist communities on the island of Ireland since partition. Thousands of young people and adults were experiencing life across the border for the first time under the auspices of Co-operation North’s Schools, Youth and Community exchanges. Other popular activities, like the Maracycle (which at its height was attracting over 4,500 amateur cyclists on a weekend long round trip between Dublin and Belfast), also facilitated the largescale development of new cross border contacts and relations.

A thriving Business Programme produced innovations, like the first North-South public procurement directory. And it developed strategies that included proposals for a series of cross border cooperative programmes in the public sector (North-South Units) that found fuller expression in the six Implementation Bodies that emerged from the Good Friday Agreement under the auspices of the North-South Ministerial Council almost 20 years later in 1998. O’Regan was two decades ahead of his time!

The organisation evolved from the basic contact hypothesis phase to a more interventionist phase. Exchanges addressed more directly issues of prejudice and sectarianism, and embraced specific conflict resolution solutions.

Simultaneously, Brendan’s quest for peace was not confined to the island of Ireland. In 1984, he founded the Irish Peace Institute, in partnership with the National Institute for Higher Education in Limerick (now the Unversity of Limerick). It aimed to harness “intellectual and academic talent towards understanding the phenomenon of conflict and proposing initiatives that designed to increase the prospects for peace on the island of Ireland.” (Dr. Ed Walsh, 2017). The Institute’s programme included joint peace studies courses with the University of Ulster, as well as the world’s first ever international peace conference in 1986.

In 1985, Brendan established The Centre for International Co-operation, which embraced an international dimension to peace building. His earlier pioneering work in developing Shannon as a unique international hub for transport and aviation, during the Cold War period undoubtedly influenced this train of thought. The credibility he had earned with stakeholders from his Shannon Development days ensured he could enlist serious private sector, state and semi-state support for this latest venture.

Aer Lingus, Aer Rianta, GPA, SFADCO and others added practical financial and other logistical support. World leaders attended major events, which sought to explore how international Co-operation in the quest for peace could be practically advanced. At one such event in 1988, “Global Communications – A Network of Co-operation” in Dromoland Castle, initial contact was established with an influential diplomat from the Soviet Republic of Estonia. In the earlier part of 2019, Estonian and Irish musicians celebrated the 30-year friendship, which arose from this initial encounter.

Brendan undertook these three major peace initiatives with the support of one man in particular who shared his vision for Irish and global peace, security and co-operation. Chuck Feeney was a billionaire philanthropist whose Duty Free Shoppers Group was influenced by Brendan’s pioneering operation in Shannon. Feeney for many years gave generous support to all Brendan’s peace initiatives, under strict anonymity.

Brendan thought the unthinkable, then persuaded others to help make it happen. Directly and indirectly, Brendan’s work has found expression in local, national and international peace, reconciliation and conflict resolution scenarios. The world is undoubtedly a better place for the vision of BOR, as those who had the privilege to work closely with him affectionately knew him. Buíochas, Brendan.

Peace Activist, Folklorist and Uilleann Piper Tommy Fegan first got to know Brendan O’Regan when serving as Deputy CEO, Co-operation Ireland, Ireland’s leading peace organisation. Tommy has worked for over 35 years at senior management level in the youth, education and training sectors, public, private and voluntary, in Ireland, North and South. These included Director, Northern Ireland, Prince’s Trust, Director, North- South Exchange Consortium. He is currently Director of the Thomas D’Arcy McGee Summer School in Carlingford and Chairman of CRY (Cardiac Risk in the Young).